Using her voice for good

Monreal named Scott Award winner — first-ever for RCC

It’s May 2022 and Kassandra Ciriza Monreal is on stage for the Randolph Community College Curriculum Graduation. The Presidential Scholar isn’t wearing the blue cap and gown (yet — that’ll come next year), and her dress belies a hitch in her gait. She walks deliberately to the podium to deliver the ceremony’s invocation. Although she’s dramatically shorter than the soon-to-retire President of the College, she doesn’t adjust the microphone.

She doesn’t need to.

Monreal’s voice carries over the crowd, strong and clear — something she learned from her public speaking teacher in Mexico.

She returns to her seat on the stage, flashing her signature wide smile at the next speaker.

It’s impossible to tell from the brief appearance that Monreal has been through more than most 20-year-olds — something that could have dimmed her shine and stifled her voice.

It hasn’t.

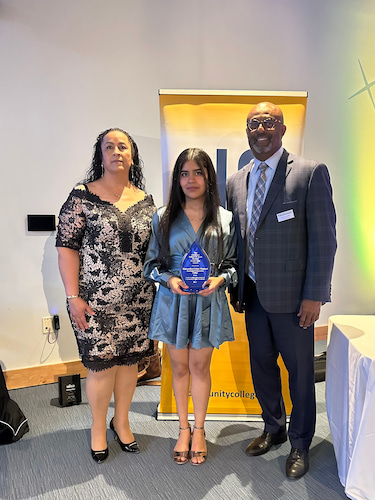

On April 20, Monreal was introduced as the Governor Robert W. Scott Leadership Award winner — the first-ever honor for Randolph Community College. The North Carolina Association of Community College Presidents created the award in 2004 to both recognize student leadership on a statewide level and honor former Gov. Scott, who served as the State’s chief executive from 1968-1972 and then as president of the North Carolina Community College System from 1983-1995. The award highlights outstanding curriculum student leadership and service.

The same week, Monreal learned she had been accepted into her top choice — the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In May she found herself back at the podium delivering the invocation and the opening remarks for the 2023 Curriculum Graduation, this time in her cap and gown, and at her final RCC Board of Trustees meeting as Student Government Association President (SGA), receiving a plaque from the grateful group.

With all the awards and accolades, Monreal could let the attention go to her head, but she has never forgotten her humble beginnings that keep her grounded.

***

Monreal was born in the United States in 2003, but moved to Mexico with her mother, Margarita Monreal Alfaro, when she was still a baby. She spent her childhood in Aguascalientes, a small mining town in the center of the country.

Born with spina bifida, she had to undergo multiple surgeries, the first when she was two weeks old, to help correct her spine and legs.

“It was hard,” Monreal said. “My parents treated me like a crystal kid. ‘You can’t run. You can’t do that.’ ”

That’s why she gravitated toward the arts — they were safe and didn’t cause her pain.

“But it also helped my personality — to be able to be more conscious and have more empathy for people,” she said.

The admittedly extroverted Monreal thrived at school.

“I used to do public speaking,” she said. “I had a teacher whose name is Alex; he’s one of the most important people in my life. He got me into that — and poetry and short writing, everything that had to do with culture and the social arts.

“I want to talk and present my ideas to other people and not to be silent. We all have a voice, and we all have a message. And regardless of the language we speak, it’s our purpose to spread that message to other people.”

Physical pain wasn’t the only trauma Monreal suffered as a child. Her father stayed in the States and, after her older brother moved back to the U.S. in 2017, it was just Monreal and her mother.

“It was a hard thing to think of my brother and my dad here, and we just decided to move here to try to look and see how things went,” she said.

Monreal and her mother moved back to the U.S. in 2019, near her grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins on her father’s side. She was a junior in high school when she enrolled at Southwestern Randolph High School.

“It was kind of tough,” Monreal said. “It was right after COVID hit, so it kind of disrupted my journey here in high school. It was hard to adapt, and then it was even harder because I was not able to have new interactions with people due to online school and all the requirements like social distancing. I missed a lot of experiences that you get to do in high school. But my personality is, ‘You can do it. There are no other chances. Don’t be sad about it. You’ll meet new people somewhere else.’ ”

Monreal knew some English thanks to listening to music in English as a child, but she never learned how to carry on a conversation. Her first class at Southwestern Randolph was science, and the class watched a video of Bill Nye the Science Guy.

“He spoke so fast, and none of my classmates spoke Spanish,” she said. “So, I had to find my way to understand the classes. It was kind of like a survival instinct to learn the language.”

Luckily, Monreal also was in a class taught by English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher Ursula Goldston, a 40-year veteran of the profession.

“She is one of the people who helped me the most when I came to [the U.S.],” Monreal said. “She understood my needs, and she was always there for me to ask for help, whether it was a class that I couldn’t understand or if I had a medical appointment and couldn’t attend school or a test that I was not feeling OK to take. She’s just like an angel for me.”

The feeling is mutual — Goldson said she could tell immediately there was something special about Monreal.

“She was one of those stellar students that, as a teacher, you might have the privilege to teach once or twice in your lifetime,” Goldston said. “I’ve only had one or two other students in 40 years who reached her capacity.”

In fact, Monreal maintained a perfect “A” average in high school, along with being a member of the Beta Club, 12th grade Spanish state Beta Champion, and a member of the N.C. Academic Scholar Program.

Monreal didn’t just work to improve her communication skills, however. She helped many other ESL students, taking a leadership role in Goldston’s class and helping new students even when she wasn’t in the ESL class anymore.

Monreal left the ESL program in two years, which, Goldson said, is unheard of.

“Usually, students with her history stay [in ESL] forever, especially at the high school level,” she said. “We have these long-term ESL students that just can’t pass the test. She was a high achiever when she came. She came from a very good school in Mexico. She had some English, but she struggled, of course, with the language and the whole transition. She was in culture shock, but she adjusted very well, and she graduated on time with her peers.

“I can’t wait to see what else she’s going to do. She’s one of those students — the sky’s the limit. That girl can do anything she sets her mind to.”

***

Still, doubt crept in when it was time to decide what to do after high school. Monreal said she was afraid of being rejected by a college or university, then remembered touring RCC with her ESL class and then-Director of Educational Partnerships & Initiatives Dr. Isaí Robledo. There, she learned about the Presidential Scholarship and the College’s open-door policy. Plus, RCC was close to home.

“I could still help my parents and not worry about tuition,” she said.

A self-confessed procrastinator, Monreal applied for the scholarship on the last day.

“I didn’t trust myself and my qualifications,” she said. “I remember getting the call telling me that I was a Presidential Scholar. It was really exciting.”

Once enrolled, Monreal quickly became involved in as much as she could while still concentrating on her studies, becoming a member of the Rotaract Club, Phi Theta Kappa, and SGA for which she was President this past school year.

“SGA has all these opportunities,” she said. “You get to be involved in the school environment, planning events and going to conventions and meeting people from other SGAs.

“As President, I’m a non-voting member of the Board of Trustees, and I get to attend those meetings and see how the school is going. I love that. I love being involved.”

Monreal also has leant her voice to RCC’s creative writing club, Uwharrie Dreams, winning writing contests and being featured in several publications, including the most recent, “When I Say We — Stories of Family, Culture, and Traditions.” Monreal contributed a poem, “Latitude,” and a flan recipe to the publication and was the student poetry winner.

“There is a saying in Mexico ‘the sun doesn’t burn here as it does there’ — my skin is lighter now because I don’t go out much,” she said. “In Mexico, I was outside all the time, walking to all the places. I had to walk to school, to go home, to go visit my friends. So, there was a lot of sunlight hitting my skin. Here, it’s really different. You’re isolated. You’re home all the time or you’re at work. But, in my poem, I say, “Maybe my tanned skin/Lost its tint on the journey, but the blood flows in me like a rampaging river stained by the clay that hides beneath the soil.’

“It’s a way to express my feelings on how all of this change was on my mind. I couldn’t express it, so I put it into poems.”

Through her experiences at RCC, Monreal has become even more vocal.

“She’s the focus; she is the leader of the class,” RCC Chemistry Instructor Abu-Bakarr Kuyateh said. “She’s the one who speaks the most, who answers the questions the most. She is very driven, and I love that about her.”

Kuyateh said that, after the recent chemistry lab renovation, he held optional labs for extra practice. Monreal showed up for every one of them.

“It had no effect on her grade whatsoever,” he said. “We just had materials that weren’t being used. I told my students, ‘Hey, we’re gonna blow stuff up today.’ She showed up every single time — even labs that weren’t exciting — we were just making solutions. Even when I had an experiment where I just needed extra hands, she was the first one to always volunteer. Sometimes my classes are quiet, but they don’t remain quiet because she’s the first one to speak.”

The instructor understands first-hand what it’s like to get used to a new language and culture.

“I’m a first-generation American,” Kuyateh said. “Some of the words I use weren’t English when I was starting out school. English is her second language, but she’s still so vocal and she’s very confident in her language skills. She has a voice.”

Kuyateh said that it all comes from confidence.

“She’s very self-aware, and a lot of students her age don’t have that confidence,” he said. “Even the way she stands, she doesn’t even have to speak. She knows, ‘I’m awesome, and I’m going to let the world know.’ She oozes confidence. No one needs to give it to her.”

Monreal is immensely proud of her Mexican heritage.

“She talks about Mexico all the time because she’s so proud of it,” Kuyateh said. “She’s not shy to hide the fact that, ‘Yeah, English is my second language and I’m killing it still.’ She’s willing to share her culture.”

While confident, Kuyateh said that Monreal is always willing to help her fellow classmates.

“She’s also very humble,” he said. “She doesn’t belittle students. A lot of students look up to her, to be honest. When they are struggling, especially in lab, I don’t have to say anything. Students go to her, and she’ll explain what’s going on. Once again, English is not her first language, and she’ll make the students understand better than I do.”

Kuyateh has a theory why that is: “I think that’s because they’re the same age. When I speak, they don’t hear me. When she speaks, they all hear her. I think that’s great.”

Tutoring comes naturally for Monreal, who made the RCC President’s List four times and earned the Academic Award and the Curriculum Award in 2023.

“I pick up on things really fast,” she said. “So, I started learning the language quickly, and I started saying, ‘Hey, you should try this’ or ‘Hey, you don’t understand; just ask for help. I can translate for you, or I can teach you how to do it in Spanish.’

“[Tutoring] is a hard task, but it’s really rewarding. The other day, I had just finished helping one of my students for Spanish and he got an A. I’m proud of him, and I’m proud of myself because teaching is not easy.”

***

There is another person who is extremely proud of Monreal — her mom. In Monreal’s essay in the Presidential Scholar application, she chose her mom as her hero.

“She is one of seven kids,” Monreal said. “It was hard for her to access education, but she managed to finish a technical level to be a secretary. I remember when I was asked, ‘What do you want to be?’ I always said I wanted to be a secretary. She always supports me no matter what.”

That support will stay even if Monreal doesn’t choose the secretarial path and becomes an immigration lawyer.

“Growing up, I never had this passion for something or settling on something; I was always trying new things,” she said. "For example, I love playing the piano. I love plastic arts. So, when it came time to decide which career I wanted, it was a hard decision to make.

“But I’ve always loved to help people. I want to pursue law. My parents are immigrants. They are residents of the U.S., but many workers are not. They should be treated with dignity because they give a lot to this country.”

No doubt Monreal will use her voice so they will be heard — loud and clear.